uncaring: reflections on the politics of literary translation

I wrote the word “uncaring” on a torn piece of paper the other day, a gesture stirred by the world we currently live in. As I was reading one social media post here, a newspaper opinion piece there; I grabbed one of my many fountain pens which I delicately fill with ink stored in glass bottles (writing needs its own pace) and marked the red paper. “Uncaring”, I read out loud as I placed the paper on one of my library shelves, the one with the non-fiction books. Every day, I look at the black ink on the red paper as rage boils in my heart, mind and soul. I am tempted to join the online cacophony of what makes me angry. But I decide to wait and reflect (writing needs its own pace).

pages from my notebook where I started drafting this essay

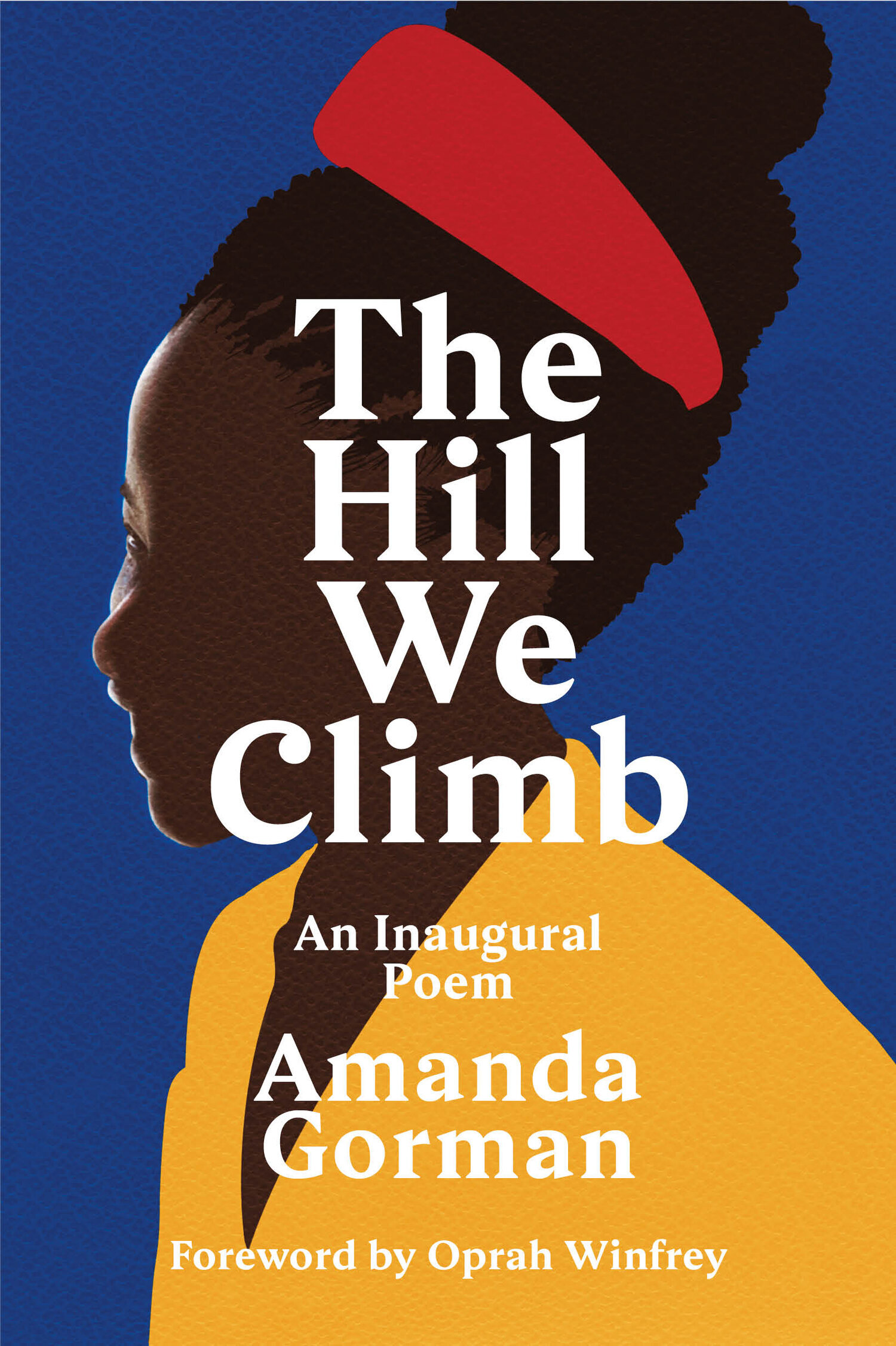

I am perplexed and disheartened as I read the many reactions fuelled with hatred and ignorance about the decision by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld to not translate Amanda Gorman’s inaugural poem The Hill We Climb into Dutch. I am appalled at the way it has been framed in the international media, as a case of political correctness, avoiding the whole context the debate started in, with headlines like “’Shocked by the uproar’: Amanda Gorman’s white translator quits” in UK’s The Guardian or “Amanda Gorman : une autrice blanche pour la traduire ? Polémique aux Pays-Bas” (“Amanda Gorman: a white female author [sic] to translate her? Controversy in the Netherlands”) in French Le Point, misgendering Rijneveld nonetheless, “Dutch writer will not translate Amanda Gorman’s poem after ‘uproar’ that a white author was selected” in USA Today. While one may not be surprised at the copy/paste culture and sensationalism of most media coverage, similar simplified discourses were also expressed within the international literary translator’s community in a closed Facebook group which counts more than 4000 members. While many focused on criticizing the choice for someone who has no experience in literary translation (which is a valid point but completely disregards the context, as I will explain later), others also cried out political correctness and cancel culture.

There is a lot of noise made in the pursuit of instant gratification by way too many uncaring voices.

Writing the word uncaring on that piece of paper and putting it in plain sight of my daily life, was a materialisation of my feelings about what is currently going on in our world. Politicians ignoring the most marginalised communities throughout their decision making, policies pushing the more vulnerable into more precarious situations, systemic racism unacknowledged in many industries – including culture and publishing, people partying in parks disregarding pandemic regulations, entrepreneurs and café owners shouting their distress as if lockdown was only affecting them, discourses focusing on the need to open the economy while ignoring culture and lacking to give proper support to the health sector. In our neo-liberal societies, making profit remains the ultimate goal, even as the world counts more than 2 million deaths from the coronavirus. No wonder people, institutions and businesses act and express themselves with no care. An individualist society tends to be an uncaring one.

The many uncaring voices expressing themselves across online platforms regarding the translation of Amanda Gorman’s poetry into Dutch are fuelled by this system. I am not taking away their agency and blaming the political and economic environment only, they are responsible for their actions and opinions. I am interested in how I can challenge their views in a way that does not ignore the external factors influencing us all as we build discourses. And I thrive to contribute to those that push to learn and evolve, instead of polarizing. Not acknowledging the political and cultural context in which this particular publishing operation happens, as well as the economic reality of publishing in general – like most of these uncaring voices have done, is simplifying the situation and silencing any possibility to move further into the real, systemic issues.

To be clear, most of the criticism against the choice made by the publisher of Gorman’s work in Dutch did not say that literary translators need to have the exact same identities and experiences as the author, and therefore that no white person can ever translate a black author. They rightfully challenged the publisher’s choice in a context of ongoing systemic racism against non-white Dutch voices, and especially black ones.

They demanded that they care.

Many of the cultural institutions, including literary publishers, have put on black squares all over their social media back in June, claiming they were allies in the Black Lives Matter Movement. Now, they fail massively in putting into practice what they preached back then. For them, it was just a slogan, for the black people in this country, it is their reality, their lives.

This whole debate also shows, once again, that very few people (including all the columnists who cry “cancel culture”) understand how literary translation works. Literary translation does not happen in a vacuum, choices are made on all levels of the publishing process. In this case, choosing an International Booker Prize-winning author was primarily a profit-oriented choice. Publishing is business. Business does not prioritize solidarity.

I have been a literary translator for two decades, I have written and given many talks about the politics of translation, developed projects which tackle exactly this very problem: who translates who matters; you translate with your biography. I did this from my own perspective and background as the daughter of Turkish-Muslim immigrants in Western Europe. I am now talking from this perspective and from the knowledge I have of the literary industry in several European countries.

Unsurprisingly, whenever I spoke out advocating the role of translation to defend and support freedom of expression, criticising the politics of oppression happening in my country of birth, I was received with open arms in Western European literary circles. However, when my discourse moved to the inclusion of translators with immigrant backgrounds into these circles, questioning why there were so few of us in the world of literary translation, it quickly became uncomfortable, and attempts to silence my voice were made using the “mother tongue” argument (which thankfully is being invalidated more and more, but it wasn’t always the case). I am therefore not surprised by the many “political correctness” outcries from mostly white Dutch commentators. Remember, this is a country where we are still debating if blackface should be banned from the yearly Sinterklaas children celebration (search for Zwarte Piet if you want to learn more).

Translation happens in a historical, political and cultural context. Language evolves across time, societies change. Thankfully, we evolve as humanity. So do our translation practices.

There is a good reason why classics need to be retranslated regularly (if you are interested in this topic, do check the many articles that came out about Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey in English).

A translator will make choices based on their life experience and their identity (so yes, race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, socio-economic background, disabilities… will matter), and so will the fluidity of these. Of course, knowledge of the craft itself is important, but it is not always enough. Not all types of work require the same kind of approach to literary translation.

I personally translate with an urgency that many translators from Turkish who have fallen in love with my birth country after a visit to Ephesus have not. Our reasons for becoming translators come from different places – cultural, socio-economical or political. One is not better than the other, it is just different, and so different works of literature will necessitate different types of translators (also, don’t underestimate the role of editors in the process).

In European Others. Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe, Fatima El-Tayeb writes:

The national often is the means by which exclusion takes place; minorities are positioned beyond the horizon of national politics, culture, and history, frozen in the state of migration through the permanent designation of another, foreign nationality that allows their definition as not Danish, Spanish, Hungarian, etc.

This state of being constantly “frozen in migration” through discriminatory practices on different levels – personal, institutional, economic, political – is one I recognize. My immigrant background has been highly influential in shaping the translator I am today, and also my urge to translate certain works more than others. And to advocate for more diversity in literary translation in the European context, as to include as many “European Others” as possible.

Amanda Gorman’s poetry falls into the category where the political context matters greatly, and the translation of her poetry is a possibility to break through the “frozen state” of many identities, elevated and silenced at the comfort and benefit of the dominant gatekeepers. As we breathe new languages into her experience and imagination, we should care to create space for inclusion and recognition.

She also comes from the spoken word tradition, which offers a different set of challenges when it comes to translation and will necessitate someone who is familiar with how it works both on stage and on paper. By asking Rijneveld, the publisher clearly ignores this key aspect of the craft, and therefore shows once again that their motivation is primarily a commercial one. The translator of a work like Gorman’s needs more than excellent writing skills, or a literary award, they need to feel her words on the different levels of their experience, as well as emotionally: inside their hearts, their soul, their body. Does it mean that a white translator could never translate her words, or any other black writer’s? Or even I, with my multicultural background? Of course not. Our variety of experiences could help us feed into our translations and even create something beautiful. But this is beside the point and again, ignoring the context we currently operate in. The reality is that there is a lack of true diversity in the literary translation realm across many Western European languages such as Dutch, French, English… So, when an opportunity arises to publish a work that tackles the black experience, it is of immense importance to go out and find a translator from the existing pool of talented black voices within the target language. In a context like this one, ignoring this option is choosing to not care. Literature is political. Poetry is political. And so is translation.

Another point that will help nuancing and understanding this whole debate is that the majority of publishers only care about the public visibility of translators when it’s good for profit (I challenge you to name any literary translator’s work you read recently). Most of the time, translators can be happy to have their names on the title page (those who print translators names on the cover are the progressive ones) or be mentioned in reviews or at literary events. #namethetranslator exists for a reason.

So, knowing how translators are usually made invisible and knowing the cultural and political context we live in (Black Lives Matter, social inequalities, climate change… oh and the pandemic making it all more clear that our systems are broken), the choice made by the Dutch publisher of Amanda Gorman shows an enormous lack of imagination (it is first and foremost a business decision), but worse, it is another manifestation of the ongoing systemic erasure of certain voices, in this particular case, black voices, from a literary industry that has made no efforts in implementing inclusive practices when it comes to literary translation.

I turn again to my sad little piece of paper which summarises the state of our world and defines the level of our discourses way too well. I try not to sigh out loud, but I can’t help it: “uncaring”.

There are yet so many layers to unpack on many fronts and we need more depth than all the cancel culture outcries and binary shallowness filling the online spaces. It would be interesting to also look at other Western European countries, such as France, where the publisher has chosen Belgian-Congolese artist Lous and the Yakuza, a famous musician and singer who is not a translator. It is legitimate to disagree with the French publisher’s choice based on the necessity to advocate for better understanding, visibility and presence of literary translators who have knowledge and expertise. But as I stated earlier, this is not enough to translate works like Amanda Gorman’s, or the works I choose to translate from Turkish. The urgency is different. Choosing someone like Lous and the Yakuza honours not only that need, but also communicates a message to the reader and the community of black poets, writers and artists that their voices matter.

In the end, all these choices highlight the huge lack of diversity in the literary industry, especially among literary translators. The problem is once again one of representation, as well as accessibility, and therefore: power. Who gets to tell which stories and how, matters, as well as who translates them for whom, and in which context.

The current levels of uncaring in our societies necessitate a deeper and more honest look at how these decisions are made and if there is space for diversity and inclusion in profit-oriented practices. We need to do better. We need to truly care.

This essay was written for the International Literature Festival Read My World where the author is a programmes curator, on 4 March 2021. Following its huge success online, Canan published it in French for Diacritik on 8 March 2021, where it was also widely shared.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes a newsletter and podcast titled The Attention Span, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture.