Freeing the Unspeakable: Artists Take Control of Their Stories through Comics

What does it mean to read and make comics in the #MeToo era? To try to understand how issues around sexual harassment and gender-based violence are represented in comics, we look at the work of artists and collectives from eight countries. Ranging from autobiography, reportage, satirical cartoon, fiction, webcomic, and even including superheroes, these stories remind us of the universality of the issue. To change attitudes we need to start changing culture. Comics offer many spaces of expression to lead the conversation.

“From Paris to Cairo, from Yorkshire to Istanbul, from California to Casablanca, … women are raising their voices against oppressive cultures denying their right to speak up. The invisible becomes visible as we all learn together to open the spaces of creativity to all.”

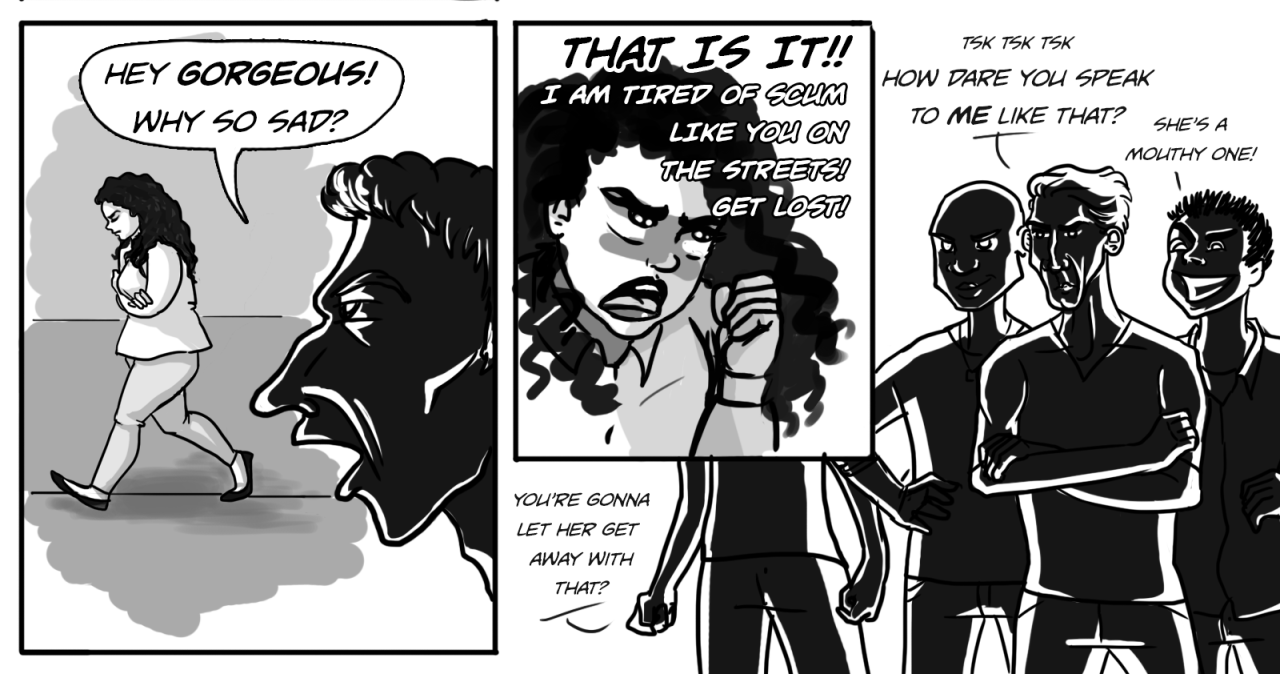

‘Take it as a compliment’ is a disturbingly common sentence many women – and some men – have heard as they were being harassed. And if not uttered as such, it has been the hidden message society kept reminding whomever would dare to openly share their experience of sexual abuse, violence or harassment, let alone publicly condemn it. Throughout centuries and across geographies, women have been silenced or conditioned to accept that such experiences will happen to them no matter what, and that they better learn to ‘take it as a compliment’. It is no surprise that the title of Scotland-based illustrator Maria Stoian’s powerful collective graphic memoir published in 2015, gathering stories of sexual harassment is titled Take it as a compliment. Stoian’s collection is made of interviews and anonymous messages received from women and men across the globe. Each story is another heart-breaking and infuriating account of someone’s real-life experience with sexual harassment, violence, or misconduct, and a harsh reminder of many people, and mostly women’s, daily encounters in public space or in the privacy of their homes. Through this award-winning collection of stories, Stoian reclaims the sentence and all the societal baggage it carries by making these experiences visible.

#MeToo and Comics

“There are many levels of sexual and gender-based violence as these many comics show, and they are all depicted differently depending on the context in which the work was created. Whether autobiographical, fictional, or rendering other people’s stories, each single comic is created out of an urgency to show the unspeakable, to create a space for overcoming trauma, and allow empowerment.”

Last year, the viral hashtag #MeToo has created an unprecedented momentum across industries thanks to the power of social media. From Hollywood stars to our own closest friends, the number of women who have experienced any level of sexual violence – from street harassment to rape – found a way to express their anger. Time magazine even made these ‘Silence Breakers’ Person of the Year 2017. It took more than ten years for these two words first used by civil rights activist Tarana Burke to raise awareness of the pervasiveness of sexual abuse and assault in society, to finally find global recognition. “The women and men who have broken their silence span all races, all income classes, all occupations and virtually all corners of the globe,” states the Time article. We now live in the #MeToo era, which pushes all of us, regardless of our gender, to look at the way society treats sexual encounters with a critical eye, while remembering that survivors of sexual violence in any form have been here for centuries. The main difference today is that: we can access their stories. The world of comics has not been isolated from this global movement, #MeToo allowed comics creators and readers to share their experiences of sexual misconduct, harassment or violence, whether within or outside of the comics industry. The Mary Sue online magazine offers an unsurprising yet necessary account of “Harassment and Sexual Assault in the Comics Industry” in the form of a brief timeline. It starts in 1944 with Julius Schwartz - known affectionately as ‘Uncle Julie’- editor of Superman, Batman, and many other highly popular comics. Sure, it was still the first half of the twentieth century, and didn’t Mad Men confirm that harassing women in the workplace – and literally anywhere – was an acceptable if not an encouraged pastime in those days? Most importantly, what the Mary Sue timeline does highlight is the continuous celebration and honouring of ‘Uncle Julie’ despite that: “Throughout his career, there are murmurs of varying volume about his unwanted advances and wandering hands, and despite repeated complaints, DC never seems to do anything to rein in his behaviour”. We have heard a similar tune about Harvey Weinstein’s attitude being an ‘open secret’ in Hollywood. This is about power, and we are still living a man’s world. #MeToo as a movement is an opportunity for societies to shift perspectives on gender-based roles and to imagine new possibilities for equality for all. In this context, comics as a medium offers a unique way for creators to take control of their own stories and make the unspeakable visible. Many women, and some men, have been doing it for more than two decades already through their comics dealing with sexual violence in different forms and on a variety of levels. Those stories were not inexistent, but in this #MeToo era, they become more relevant than ever.

Take it as a Compliment ©Maria Stoian

Beyond borders

In 1996, illustrator Debbie Drechsler publishes Daddy’s Girl (reprinted in 2008), an autobiographical collection of short comics based on the author’s childhood experience of abuse. In this heartbreaking and disgusting narrative, Drechsler does not spare the reader and renders her experience in a graphic way. The stories centre on Lily who, among her three sisters is singled out for sexual abuse by her father, an honourable man who does charitable work on the outside, and who molests his little girl behind closed doors. Lily is made to believe she is the seducer and is manipulated into feeling guilty. It is an extremely difficult read which once again reminds us of the role society plays in silencing survivors of sexual abuse under the guise of guilt and shame.

In Leïla Slimani and Laeticia Coryn’s graphic novel Paroles d’honneur, we see prominent Egyptian-American feminist and writer Mona Eltahawy telling the Goncourt winning novelist Slimani on the importance for women to tell their stories. In this BD reportage, Slimani speaks to women in her native Morocco and gathers their personal stories about sexuality and love. The work highlights the omnipresent hypocrisy of a society more interested in keeping appearances rather than allowing people’s, and especially women’s right to happiness and dignity.

Paroles d’honneur. ©Leïla Slimani and Laeticia Coryn

The necessity to talk about one’s experiences is essential in challenging patriarchal tendencies and in breaking taboos, both of which know no borders. The pressure women face to remain silent on all sorts of topics related to sexuality falls even worse on survivors of sexual violence.

Cover of Bayan Yani, March 2018.

Turkish comics magazine Bayan Yanı’s name literally translates as ‘the women’s side’. It is also a reference to a form of segregation on inter-city busses in Turkey: women cannot sit next to men they are not related to, and therefore need a bayan yanı type of ticket. The very title of this monthly magazine led by women comics artists and writers, and showcasing women’s work, has highlighted stories related to women’s rights in Turkey since its inception in March 2011. Whether it is domestic violence, street harassment, child marriage or honour killings and other misogynistic murders, these comics have been a bubble of oxygen and much necessary space of freedom for women not only to express themselves but to create awareness, connect and empower each other through comics.

Creating Super Heroines in a Male Dominated Culture

Empowerment leads to transformation, UK-based comics artist and scholar Sarah Lightman writes in her essay about the portrayal of trauma in autobiographical comics where she interviews Maureen Burdock, the author of Mona & The Little Smile. This work relates the author’s own story of being abused as a child. Burdock tells Lightman that comics is the perfect way to tell a story in an accessible and engaging way: “Even traumatic narratives acquire a depth and often humour when they are told in the comics format. I was also drawn to the idea of creating super heroines – imbuing my female protagonists with special powers.”

This is also what Deena Mohamed does with her webcomic Qahera, which, as Mohamed explains on her website, is: “the female form of the word ‘qaher’ in Arabic, which means ‘vanquisher’ or ‘conqueror’ or ‘triumphant’ (basically a lot of cool things). if you add ‘al’ to it, it becomes ‘al qahera’ which means Cairo, the capital of Egypt.” Qahera is the superheroine that fights for social justice and equality in the streets of Cairo. She is strong, she can fight and she can fly. These short comics touch on major issues related to the place of women in Egyptian society, and one story specifically tackles street harassment.

“What kind of comics culture do we want to build in the age of #MeToo? As creators and as readers, we all have a role to play. Could comics, through their accessibility, possibility to tell bold imaginative as well as true stories, and their capacity to go beyond the expected discourses, lead the way towards building an equal society?”

Just like we also learn in Paroles d’honneur or in the stories shared in Bayan Yanı, how much a woman covers herself up does not matter: harassment and sexual assault happen to any woman, in public space as well as behind closed doors. A few years before Deena Mohamed, in 2008, Egyptian artist Ahmed Makhlouf had created another superhero: Super Makh. This character wearing a floral print cape and chewing cinnamon gum reappeared in Egyptian comics magazine Tok Tok in 2013, two years after the revolution. Super Makh’s main goal is to help women and girls fight sexual harassers.

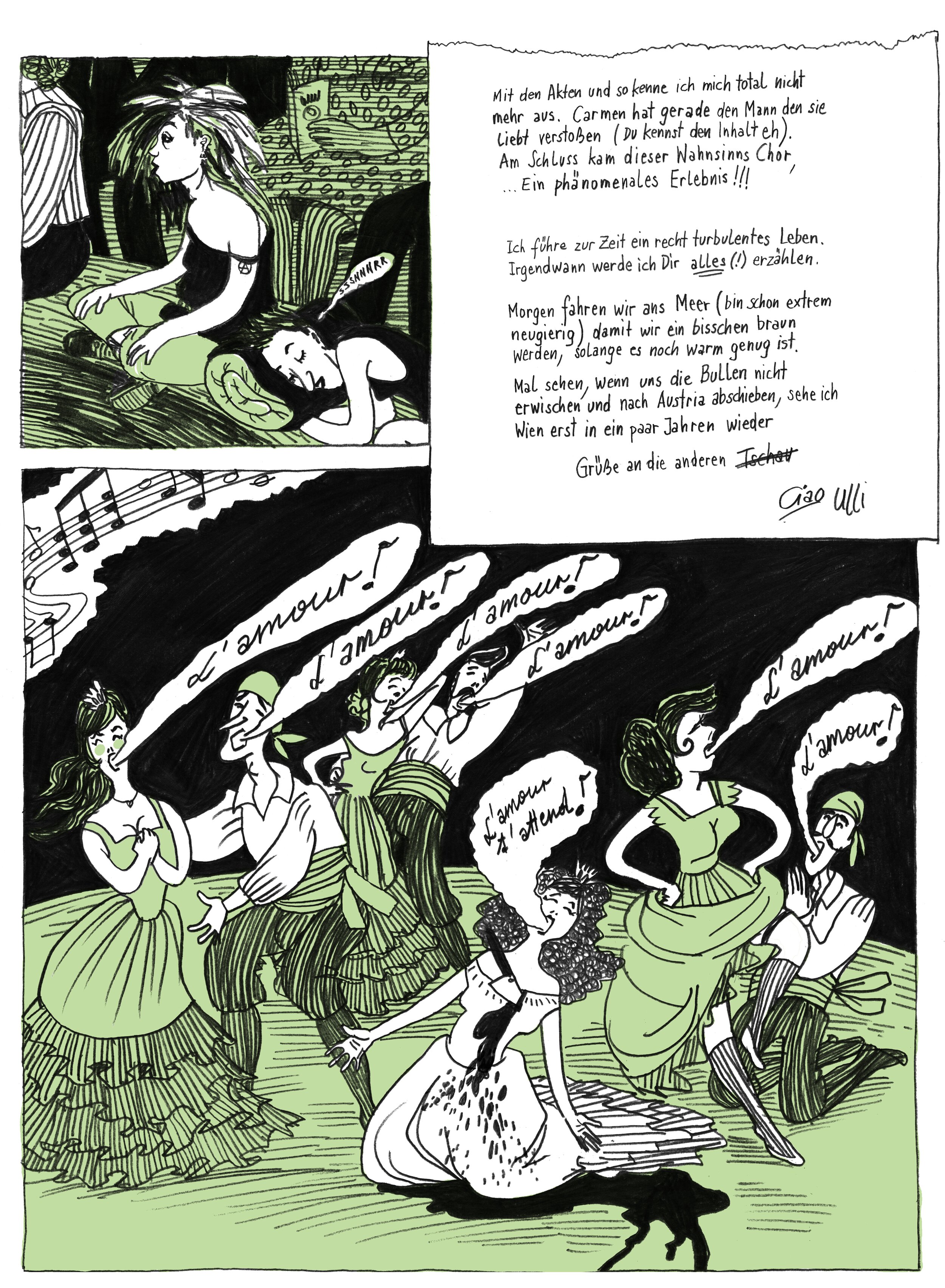

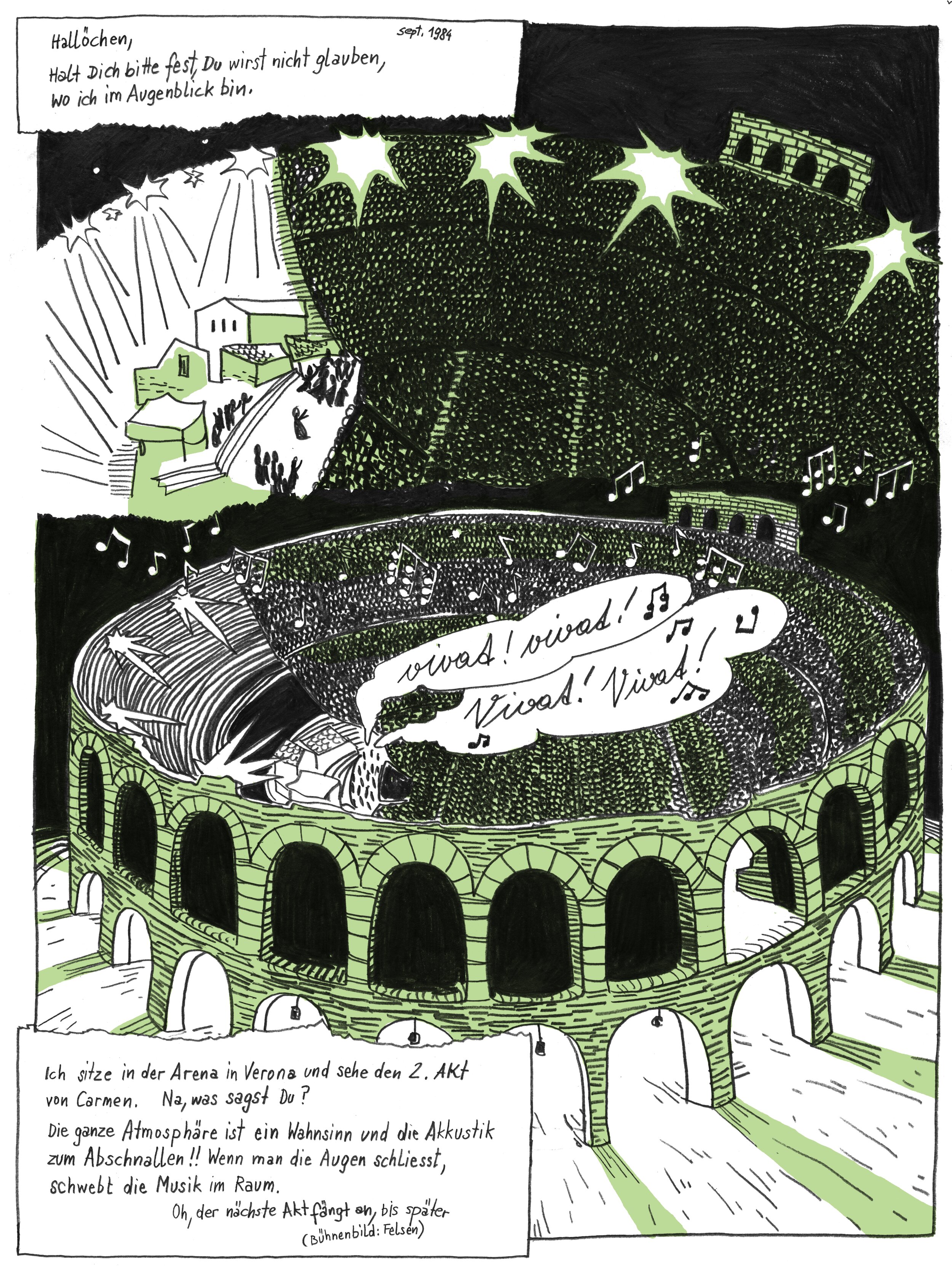

It would be wrong to think that street harassment and taboos around sexuality only exist in certain parts of the world. Berlin-based comics artist Ulli Lust has recounted her younger years in her award-winning graphic novel Today is the Last Day of Your Life (translated by Kim Thompson). Her story takes us to 1984 where we follow 17-year-old punk Ulli as she hitchhikes with a friend across Italy, both penniless and adventurous. Lust renders her days on the road humping from place to place in a very meticulous way and manages to capture the anxiety and excitement created by the unknown. Without ever victimizing herself, she does present the very dark side of being a girl on the road, constantly turned into a piece of meat under an incessant male gaze. Ulli encounters many men, she even likes a few. At some point, sex becomes an exchange currency for a place to stay or some food. Even if sometimes she does enjoy the sex she has, we do see her being pressured into sex by a very normalized attitude to sexual assault. According to these men, a decent woman would refuse anyway. But even when she says no, consent is silenced, and at one point, she gets violently raped. One panel following this horrific scene is extremely moving: we see Ulli’s silhouette and two thought bubbles appear: “I’ve got to withdraw”, “I’ve got to disappear” as the silhouette disappears under the silence to leave only three lines to contour an almost erased Ulli.

Another devastating personal account is offered by UK-based comics artist Una, with Becoming Unbecoming. This story takes place in the decade prior to Lust’s road trip: we are in 1977 when Una is twelve years old, and this time, we are in West Yorkshire where the police is on a man-hunt to find a killer of prostitutes. While this story becomes national news fascinating the masses, Una experiences gender-based violence herself. In her work, Una challenges the overall culture in which male violence not only is unquestioned and goes unpunished but is also celebrated.

Becoming, Unbecoming ©Una

Ulli Lust also refers to the representation of gender violence in culture, albeit very subtly, in her own story as we see her listening to the opera Carmen. The young Ulli poses no judgment, but Ulli the artist may very well be making a statement as we see Carmen stabbed in the heart while she sings “L’amour t’attend”.

A male-dominated culture in which sex is a currency and where men almost never need to think about consent is bluntly illustrated in Maarten Vande Wiele’s Paris. This story in two parts: I love Paris and I hate Paris, depicts the world of fashion in an original way, and as Paul Gravett puts it, offers “a fresh and frank satirical twist to the cliché fashion victim”. While satire is omnipresent, one cannot read this work today without putting it back in the context of the silencing of women’s voices across industries, especially when we see throughout Paris how intensely misogynistic discourses have been internalized and perpetuated by women. It is another wake up call for women and men working in prestigious and elite industries such as fashion and cinema, but also one for all those yearning to capture the lives of these women selling nothing else but a sordid dream. Sexual violence knows no geographical nor any kind of borders.

Breaking the Silence

Throughout these comics we see the importance of breaking the silence as a way to overcome trauma, and to empower creators as well as readers. Such is also the graphic novel Silencieuses by France-based Sibylline Meynet and Switzerland-based Salomé Joly. Just like Maria Stoian’s Take it as a Compliment, Meynet and Joly’s work is based on real stories which Joly collected from friends and people on social media. Each story tells of a different woman victim of street harassment. In a video interview, Joly explains that she wanted to shine a light on the issue which she realised was universal and was treated as commonplace, something she is challenging with this comic. The title Silent Women highlights the fact that women and girls are constantly being silenced by society, as we have seen throughout all the comics presented here. The visual expressions of their traumatic experiences are key in empowering them.

From Awareness to Action

Social media plays a significant role not only in sharing stories and building solidarity across frontiers, internet is also a space of creation, as we have seen with Qahera. While not only focusing on issues related to sexual violence, France-based illustrator Emma has been publishing stories online to create awareness about feminist questions, and challenging gender roles in our societies. She has responded critically to the anti #MeToo letter signed by famous French women led by Catherine Deneuve defending the right of men to hit on women. It is therefore interesting to also look at all this from the perspective of a man: Through his project Crocodiles, Thomas Mathieu has been illustrating testimonials from women related to street harassment, machismo and ordinary sexism. His work is part of this broader movement creating awareness about gender-based violence and inequalities. It also joins the work of a new generation of feminists who use the internet to reflect and inform on concepts such as slut-shaming and male privilege. Mathieu explains on Le Lombard’s website that he has been drawing the crocodiles because he also wanted to understand these major issues, which he rarely has to face as a man: “drawing these images forces me to imagine myself in the place of the female protagonists”.

There are many levels of sexual and gender-based violence as these many comics show, and they are all depicted differently depending on the context in which the work was created. Whether autobiographical, fictional, or rendering other people’s stories, each single comic is created out of an urgency to show the unspeakable, to create a space for overcoming trauma, and allow empowerment. As Sarah Lightman writes in her essay, “These everyday stories that previously had been silenced, or kept hidden in cultures of silence, find a voice and a space on the comics’ page.” Artists and writers respond creatively to painful and complex issues which are pressing, today more than ever. But it is not always easy to speak out such truths. Social media has also created a pressure to participate in #MeToo. Five comics artists have voiced their concern of being forced into performing their trauma, which they published online. Taking control of one’s voice and expressing it through comics has no doubt an empowering and healing effect, however, survivors should have the freedom to act as they choose to.

What kind of comics culture do we want to build in the age of #MeToo? As creators and as readers, we all have a role to play. Could comics, through their accessibility, possibility to tell bold imaginative as well as true stories, and their capacity to go beyond the expected discourses, lead the way towards building an equal society? It seems like many people believe so, as #MeToo comics anthologies are being prepared in Sweden, the UK and most probably elsewhere, and works highlighting the importance of feminism, such as Féministes : Récits militants sur la cause des femmes, recently published by éditions Vide Cocagne in France have hit the shelves. From Paris to Cairo, from Yorkshire to Istanbul, from California to Casablanca, … women are raising their voices against oppressive cultures denying their right to speak up. The invisible becomes visible as we all learn together to open the spaces of creativity to all.

References:

Baci, Aria. “A Brief Timeline of Harassment and Sexual Assault in the Comics Industry”, The Mary Sue, updated 29 November 2017.

Lightman, Sarah. “Metamorphosing Difficulties: The Portrayal of Trauma in Autobiographical Comics” in Stroinska, Magda., Vikki Cecchetto, and Kate Szymanski. The Unspeakable: Narratives of Trauma. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2014.

Stephanie Zacharek, Eliana Dockterman and Haley Sweetland Edwards, TIME Person of the Year 2017: “The Silent Breakers”, TIME Magazine, 2017.

I’m Tired of Performing Trauma: Five Cartoonists on #MeToo, The Response, 27 October 2017

This essay was originally commissioned and published in print in issue #3 (June 2018) of StripGids (a Flemish Comics Magazine) in Dutch (translated by Lieven De Maeyer). It is published in English for the first time on The Attention Span.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes The Attention Span Newsletter, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture; and City in Translation, fostering discourse and conversations around the art of translation.