Snapshots of a Comics Artist: Conversation with Beldan Sezen

Beldan Sezen is a comics artist and visual storyteller based in Amsterdam and New York. Daughter of migrant workers, she grew up in Germany. In her second graphic novel, Snapshots of a Girl, published in English in 2015, Sezen tells the story of her coming out as a gay woman, through a series of fragmented moments of her life. These snapshots beautifully capture Sezen’s sensitivity, creativity and talent as an artist and a writer. We meet in the old Jewish neighbourhood of Amsterdam to discuss LGBTQ+ questions, identity and how comics can take us beyond all kinds of borders.

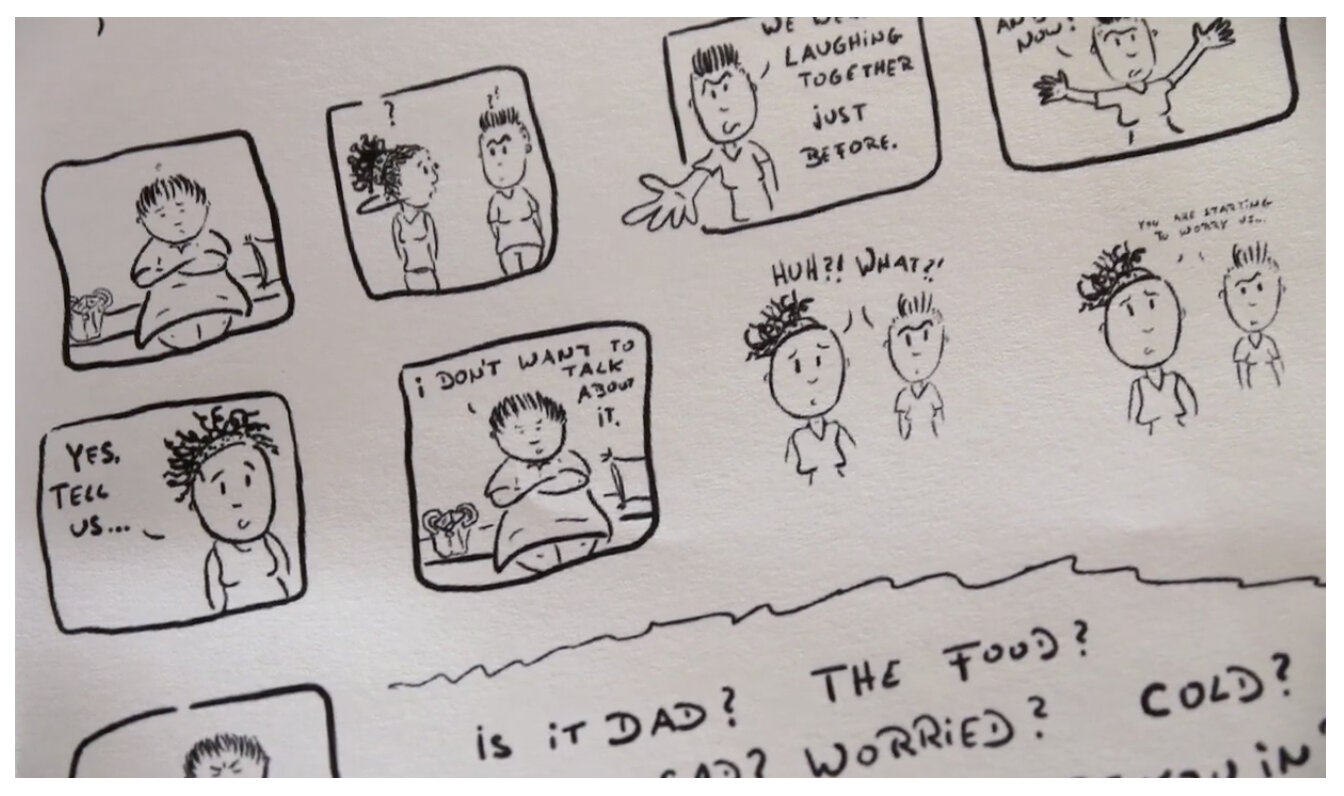

a page from Snapshots of a Girl by Beldan Sezen.

“I think identities are like labels, you use them to communicate.”

Surrounded by the neighbourhood’s rich and painful history, we immediately jump into the question of identity, its multiplicity and fluidity. Sezen has lived in several cities and continues to move a lot these days for her projects, “I’m pretty much the same person wherever I go. In one chapter of the book I talk about labels – I think identities are like labels, you use them to communicate. And it is not so much that I change when I move from place to place, but the framework of identity changes. How I’m perceived in Istanbul is different from how I’m perceived in Germany or in New York. In Germany I am Turkish, and there I would define myself as a woman of colour. Whereas in New York, being Turkish has a totally different meaning. There I can pass as white – although I never really pass as white. I adapt because I have to deal with that framework.”

Sezen manages to express these questions beautifully through comics, a medium she loves, and especially in Snapshots of a Girl;

“I can be anything in comics, I can draw what I want and the responsibility is not with me to make the connection. I provide two pictures and in the tiny space in-between two frames, the reader makes the connection, the assumption. If I draw one person with a gun in the first frame and I draw a dead person in the next one, the reader kills that person. Comics are the best way for me to express myself.”

Sezen went to live in Istanbul for a while in the 1990’s, at that time, she had the need to search for an identity, to belong somewhere within terms defined by concepts of a nation, but now she says she doesn’t think about identity in terms of nationality anymore, “I don’t think in borders, although I must deal with them every day. It’s such a foreign concept to me now, I don’t care much about it anymore”. Sezen found the perfect medium to express such ideas: comics allow her to go beyond ideas of borders. In her graphic memoir, she plays a lot within the possibilities offered by the medium itself, illustrating this very idea that borders can be erased: she alternates between longer and shorter texts, speech bubbles and paragraphs, full-page images, frames and no frames, presenting a manifold outlook on a life story. The narrative is scattered because the subject of the book is complex.

“I was first asked by an Italian publisher – the first publisher of Snapshots, if I would write a graphic memoir. My first reaction was no! Because I felt overwhelmed and thought I had nothing to say. Then they asked me to write about my coming out, and that’s how I decided to focus on certain moments that had to do with my coming out.”

The idea of snapshots fit Sezen’s purpose perfectly. Unlike autobiographical graphic novels illustrating the artist’s life story from childhood within a specific political climate, Sezen’s moments offer a fragmented perspective from one member of the LGBTQ community through the protagonist’s adult life spanning almost two decades. Focusing on the subject was more important than writing about her life, says Sezen, who also reminds me she doesn’t represent any group but herself. However, knowing that it is still very difficult for people to come out as LGBTQ, especially in Turkey where both our families come from, wouldn’t it be a good thing if this book or Sezen herself became a role model inspiring people?

“I don’t have to be a spokesperson for a community to be a role model. I can’t deny that I have put something out into the world, a work about coming out, on being lesbian, a Turkish lesbian amidst both Islamic and Western cultures, nonetheless. Just like I tried to find role models in my own youth, I support anyone who puts this kind of work out into the world.”

Snapshots isn’t translated into Turkish yet, however, Sezen was in Istanbul last year, working on a project around Butch identities for which she received a Global Arts Fund Award by the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice. This work was published by monthly women comics magazine Bayan Yanı. But not all subjects work in every place – “cultural settings matter, and as an artist and writer, you relate to that setting.”

“Being gay was not the issue. Fitting into the structures of society was.”

It was therefore key for Sezen to be in Istanbul to explore that subject and express her own perspectives in her work.

In Snapshots, Sezen comes out to her father, her mother and her aunt. She has sent the book to her parents, and despite not understanding English, they were “very proud of it”. At one moment in her graphic memoir, Sezen writes “Being gay was not the issue. Fitting into the structures of society was.”

She illustrates this to me with the following example: Her first graphic novel, Zakkum (a graphic murder mystery) also touches on LGBTQ issues and includes a lesbian couple, and before being published, it was exhibited in her family’s hometown in Germany.

“I hung all the blown-up pages. Everyone I knew from my childhood came – my parents, family members, friends and neighbours. Being lesbian was not for one moment a problem. They were all very engaged, reading and looking, then discussing. Because it was in English, their children had to translate for them. They laughed about the ending, and me being a lesbian was not an issue. It was just beautiful.”

Maybe this type of understanding and acceptance is possible through works of art, books and stories.

“Probably, but I also think we can achieve it through being honest with who we are. Coming back to our discussion about framework, and what I also mention in Snapshots when coming out to my aunt: The problem usually is about the setting and the society we’re in. In my family, the concern was more about what would happen to me. But this is my personal experience.”

Sezen acknowledges that there are many different experiences out there and that she finds hers particularly positive. This doesn’t diminish the impact of her work and the emotional effort it must have taken to write such a book,

“It takes some courage to stand up for yourself. But if I don’t do that it doesn’t fit, and I cannot expect someone else to say who I am.”

This conversation was originally published on the Bookwitty.com website on 11 April 2017. The site has since been decommissioned.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes The Attention Span Newsletter, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture; and City in Translation, fostering discourse and conversations around the art of translation.