Write, Write, otherwise we are Lost

Amsterdam, September 2016

A friend of mine is currently visiting me from Turkey. We of course have long discussions about the state of our native country, where he lives, and where I never lived longer than two months in a row. I write and translate from that privileged position of being both an insider and an outsider. I have the advantage of being “in-between”. While I am physically in the heart of Amsterdam, my heart and mind keep going to Turkey. Back and forth, back and forth without ever slowing down the pace. As we sip some locally brewed beer, my friend tells me all the stories of o gece – “that night”. I can hear the new trauma that has now entered Turkey’s people’s lives through the trembling of his voice as he recounts moments of that night and its aftermath.

Istanbul. Photo by Canan Marasligil

Rather than recounting these stories you probably already read or seen on various mainstream, independent and social media, I’d like to focus on something else he told me. As he was explaining how difficult things were getting in ordinary people’s daily lives: common friends of ours losing their jobs, the unbearable Istanbul commutes, the lack of nature and quiet in the city, the tensions among people, the growing hatred against the Kurds, or the antipathy against the plight of Syrian refugees… I asked him if he ever was thinking of leaving Turkey. His answer was quick: no. Then he explained that there is not much hope for him to find work outside of Turkey, especially being older than 30, he would at least need a mid-senior job to be able to get a visa. But then his face got lighter, “I have another dream” he added. “If I can find enough friends to do it with me, we would like to move to a rural area, somewhere in a nice village, and start a commune.” I stopped for a few seconds to digest that idea. This is a possibility I would have never considered, as the first thing I imagined he would like to do is to leave the country and go as far away as possible. His idea made me immediately think about literature, the possibilities of invention and creativity, and how important it is to keep and create spaces for imagination, especially when your environment is literally killing you and these spaces, day after day, with matters getting worse as I type each one of these letters.

We have seen many crises and wars across our human history, and creativity has always continued to flourish in different ways. Literature has been a space for dissent and resistance. I myself have always been a strong advocate for the role of translation as an act of resistance. All the work I do is around writers and works that defy the norm and those in power. Literature for me can also be a place of hope, and that feeling has been amplified by my friend’s wish to start a commune in a Turkish village. Yes, he wants to escape the turmoil, the worries, and the sorrows, but on the other hand, he wishes to create something new, and he doesn’t want to do it alone. He needs other people to build this new space with him. It’s a collaborative act that will allow a group of people to live in peace, on their own land, and to bring good to the community among which they will settle.

I believe literature needs to be such a place: where you can allow writers and readers to escape, to invent, to live multiple lives and stories. You need those spaces where you don’t only deal with current issues and politics – these will be part of many background stories anyway. You want writers and artists to be able to go beyond reality and create these places of their imagination, so they can inspire people locally and internationally. That’s why you absolutely need those stories translated. You cannot only allow voices that deal with the political issues to be heard in English.

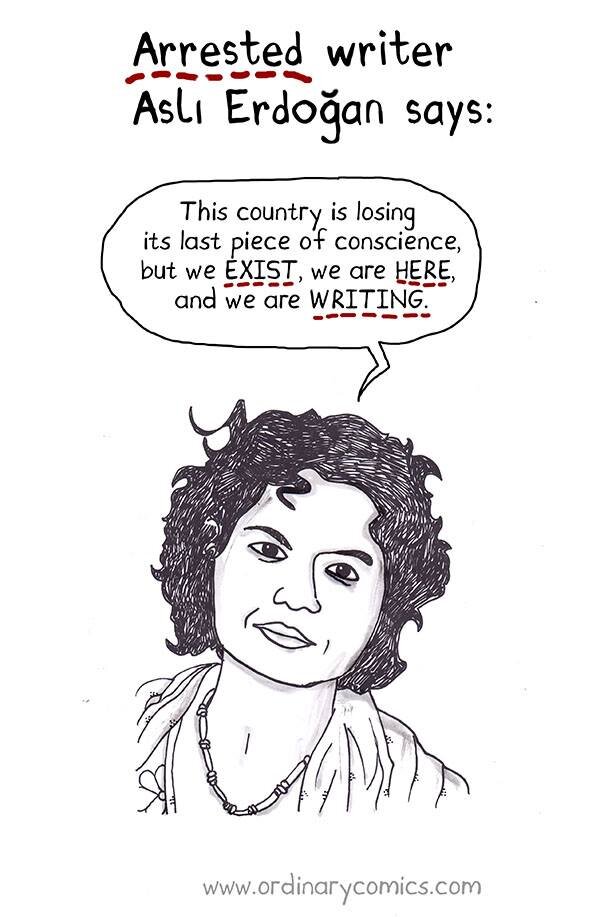

I remember Belgian historian and writer David Van Reybrouck once said: “Democracy needs imagination”, and like him, I believe that need isn’t only true in countries such as Turkey where democracy and the rule of law are coming close to inexistent, but in other places across Europe especially, where we tend to take our basic rights for granted. By creating strong literature that will be translated, we will move away from identity politics, and we will stop asking Turkish writers to comment solely on their country’s political situation. Of course, they probably care and in the case of Turkey, some are imprisoned because they care. It is the case of Aslı Erdoğan, who has been arrested and held since 16 August 2016, others, like linguist, translator and writer Necmiye Alpay are also behind bars (editor’s note on April 2021: both writers were released after four months, Aslı Erdoğan has lived in a self-imposed exile in Europe since she was allowed to leave Turkey in 2017).

Why are all these people arrested? Because they believe in peace, social justice, and basic human rights. That’s how bad things are for people in Turkey. Not just intellectuals and artists, but for every single citizen that dares to voice an opinion against the current power. So obviously, what we need isn’t just good literature. That will not solve the current war against the Kurds – many Kurdish cities in Turkey are in ruins, my friend dreaming of his commune also tells me. But I strongly believe literature, and other artistic disciplines, can give hope and create spaces for all of us to foster empathy, and in turn, build a better world. The late Pina Bausch famously said: “Dance, dance, otherwise we are lost”. I don’t think I am too naïve when I choose: “Write, Write, otherwise we are Lost” as a title for this piece. And let me tell you why I actually don’t have a choice but to remain optimistic: look at this drawing by comics artist Özge Samancı (I urge you to read her graphic novel Dare to Disappoint, in which she tells you about her own post-1980 coup childhood and teenage years, it will show you why it is worth to remain hopeful):

Image via Özge Samancı’s Facebook page.

If Aslı Erdogan, all the way from her prison cell can say “We exist, we are here and we are writing”, there only is but one response someone in such a privileged position as myself can give: “I hear you, I read you and I will translate you”.

This essay was originally commissioned by English PEN in September 2016, when I was also invited to be part of a panel on writing from Turkey, with a.o. the wonderful writer Burhan Sönmez. I have updated the piece with an editor’s note on relevant dates.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes The Attention Span Newsletter, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture; and City in Translation, fostering discourse and conversations around the art of translation.